"The naked babies stare back at you, but does that mean they have consented?"

-Dale Massiasta. Founder of the Blakhud Cultural Research Center in Klikor, Ghana

Ghana Through a White Man's Lense

In 2004, when I moved back to Ghana, one of my favorite places to go in Madina was after social welfare Taxi Rank, on the edge of the community where the houses stopped and the bush began. It was the closest my little town of 50,000 came to feeling like a village. There was a bench looking out at at a distance on an area of razed land where people dumped and burned trash. The rising smoke always gave it this kind of eery other-worldliness. All the structures were piece-mealed together. Scraps of wood and tin were bound together to form houses, fences, chicken coups, gin shacks.

I often went and sat back there alone to watch the people coming in from their farms in the evenings. At dusk, the sounds of the pentecostal church choir floated through as children carried buckets of water to their homes.

No one ever questioned me as to why I was there. Sometimes I sat alone quietly and wrote. Other times, my Ghanaian friends in the area would pull out a bench and we would share a smoke and some conversation.

Once, I brought my camera out at dusk. The smoke was rising off the trash yard and the goats were milling around. Someone had thrown out this giant television and I loved seeing an instrument of technology, this living room centerpiece so out of context--no place to plug it in and even if there were one, you had this sense that the screen would display this very yard, the smoke rising up.

I started taking pictures. I wanted to capture the order and beauty of a place where pieces of things are discarded, found and re-formed. Old car tires lie buried in the soil to mark the beginning and end of perfectly swept clay back yards. Refrigerators run on car batteries. A television is a box of glass.

That evening, a man approached me and asked me why I was taking pictures of such a dirty place. I recognized him immediately as the pastor for the church adjacent to the palm farm.

"This is why the world believes we are uncivilized," he said. "Because this is the photograph that you white people always want to take. You don't snap us wearing our nice dress, sitting in church, building schools, in our congress halls. You don't want to see us that way."

My friends tried to defend me. I told the pastor that I had been snapping all kinds of pictures--street scenes, weddings, funerals--everything! And I was even teaching children how to take pictures and document their lives. I tried to explain that I actually lived in this neighborhood, that I had been there for over a year and that I came to this spot to sit because I loved being there.

The pastor insisted I put my camera away. To him, I was any white man in Africa, all that had come before me and all that would come after. Our pictures show up in magazines with the caption "crisis" and we never show up again.

What can I tell you of my time in Ghana? I have never been calmer, never slept deeper and dreamt more vividly. I have never felt so accepted into any community. And I have never been more frustrated, more restless, alone, confused and misunderstood. There were so many times I got caught up in the desire to put a finger on something I didn't understand. To say, "oh, this is this."

I lived and worked with Ghanaians who I loved and respected. They taught me how to walk, how to dress, how to eat, how to be a host of others in our home--the rules of a culture. As a giant white infant, they forgave me when I fell down and drooled on myself. I felt for the first time what it is like for people to assume things about who I am because of my skin color. Most people were convinced before even speaking with me that I was rich, smart and lazy.

I grew to trust certain people and led them to trust me. Sometimes we disapointed each other and sometimes we found a way to give and receive on equal ground. I learned to laugh at myself. I didn't want to be the only one not laughing. I began to see that what I wanted and what I needed were completely different things. And I learned over and over, as I crashed into the same walls, to be quiet, watch and listen.

The Story being told by us to us.

"If the photographer takes the picture, the person who looks at the picture will know the truth. And will know what he can say and what he will not say. A liar will come to you and say whatever he likes, but you know that the person is lying because of the picture...if the photographer shows the picture to you and says what he saw, you will believe him."

-Edward Chao, 12 years old. Accra, Ghana.

If only some of us are holding cameras, who's story gets told? If Only some of us can get a ticket and gain visa entry to "discover" a new part of the world, what do we explorers take with us and what do we leave behind? What moving image do we see in front of us that makes us want to--click--freeze time and say, "that." That was Africa.

I was--click-- there. That was my interesting life.

At our best, Our understanding of Africa falls into neat categories that help us to sleep at night. We're in love with the idea that there is magical wisdom buried in the deep dark jungle--only the Africans know which roots and how to dig them up--and its enough knowing that this is out there somewhere. It tickles us to think about the bushman who finds the Coca Cola bottle that fell from the sky. What purity of heart he must possess. What beautiful children he has, such innocence and strength in their small bodies. We are able to believe in this man because--as the script shows-- we are flying so high above him and have accidentally convinced him that we are his God.

"As i landed in the African night..."

Our optical zoom project false proximity to a culture in which we are only visitors and to our subjects who are subjected to our instruments, our own magical powers of mass duplication. We believe discovery is our duty. And we are not surprised when our photographs tell us what we already know: it's hopeless in Africa. Hopeless without us, our technology, our opinions, our God, and our AID.

"...There, with the calloused palms of poverty laid bare before me, I began my important research..."

And so we feel we must continue to land and brave the dark jungle, to live to tell the stories from the front lines: war, starvation, humans who live in filth, children who live without, mutilations.

In high definition all of this suffering is simply immaculate.

This is what the pastor was trying to tell me. He was saying, you've already taken that picture. And while he may have made a few of his own assumptions about me as an oboroni, a white man, I agree that there needs to be a shift in point of view, a transformation in the way the west sees Africa, the way Africa is allowed to see itself. Africa is a massive continent. It is not something to be conceieved of all at once. There is vast space between the neat categories we have come to rely on. There are people walking and talking and changing and staying the same. There are millions of stories and not one of them will fit into a three column spread.

A New Narrator

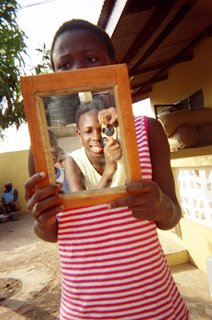

This project is the story of seventeen Ghanaian children who were given cameras by their North American English teacher and told to document their world. These were children who basically did what they were told but found a way to transform an odd assignment, a strange and foreign idea, into something that belonged to them. This was their discovery. It is not the story of Africa, West Africa, Ghana, a city called Accra, Madina, or Zongo Junction--though you will find them all there in pieces. Their assignment was never to dispel the myths of their region or enlighten the West by setting the record straight. These are fragments of a whole and should be taken as such. They snapped these pictures for themselves, for their friends and their families. They traded them in the school yard and laughed at the faces they got caught making. They bothered me daily for their next assignments.

This project is the story of seventeen Ghanaian children who were given cameras by their North American English teacher and told to document their world. These were children who basically did what they were told but found a way to transform an odd assignment, a strange and foreign idea, into something that belonged to them. This was their discovery. It is not the story of Africa, West Africa, Ghana, a city called Accra, Madina, or Zongo Junction--though you will find them all there in pieces. Their assignment was never to dispel the myths of their region or enlighten the West by setting the record straight. These are fragments of a whole and should be taken as such. They snapped these pictures for themselves, for their friends and their families. They traded them in the school yard and laughed at the faces they got caught making. They bothered me daily for their next assignments.I chose to make this site and develop this book and other ways to share their work with a larger audience because I adore these kids, and I believe that what they created together is important. I wanted them to have a record of what they did, something to hold. And I too wanted something to show for my work in Ghana, for this is also, of course, the story of my interesting life.

-SB December '06